Carrito: 0 producto Productos (vacÃo)

Sin productos

To be determined Transporte

$ 0.00 Total con IVA

Product successfully added to your shopping cart

Cantidad

Total con IVA

There are 0 items in your cart. There is 1 item in your cart.

Total productos:

Total EnvÃo To be determined

Total con IVA

Perros y otros animales

- Relojes de bolsillo y de pulsera

- Instrumentos musicales

- Banda de música y vientos de madera

- Instrumentos étnicos indios

- Guitarras, mandolinas y cuerdas

- Accesorios para violín, viola y violonchelo

- Percusión Mundial

- Latón náutico

- Cuchillos damascenados coleccionables

Novedades

-

Noble Celtic Wolf Art Solid Brass Wrist Watch Collectible. Golden.

impressive 40 mm solid brass casing with stainless steel back premium...

$ 154.04 -

Mad Magazine Alfred E. Neumann Reloj de pulsera coleccionable de latón sólido

carcasa unisex de latón macizo de 30 mm con respaldo de acero...

$ 120.62 -

The Beatles, Classic Portrait Art Coleccionable Rectangular Solid Brass Tank Reloj de pulsera

Carcasa de latón macizo de 33 mm en acabado dorado con respaldo de acero...

$ 145.89

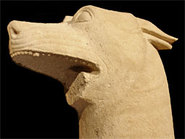

Noble Celtic Wolf Art Solid Brass Wrist Watch Collectible. Golden.

LUIGI01

Nuevo producto

- impressive 40 mm solid brass casing with stainless steel back

- premium 2040 quartz movement.

- original parchment art acrylic dial

- waterproof bracelet with brass buckle

- 1 year warranty

Más información

The Wolf in Celtic Mythologies

Der Wolf in den keltischen & romano-keltischen Mythologien

狼の神話学1

Le loup dans les mythologies celtiques & gallo-romaines

Wolf in Celtic Mythology, ancient and medieval // Der Wolf in der keltischen Mythologie // Le loup dans la mythologie celtiqueFor the 'Celts', we need to distinguish different regions of the Celtic World and different periods, notably between the Continental 'Celts' and the Insular 'Celts', between Antiquity and the post-Roman (medieval / Christian)l period. In medieval Celtic mythology (i.e. mainly Wales and Ireland, and also Britanny), where ancient myths and legends were written down in a Christianising context, wolves play a number of important roles. Similar to the Roman story of Romulus and Remus, a future king was once again reared by a she-wolf: Cormac mac Airt grew up to become an important High King of Ireland (v. infra). In many Irish/Welsh myths, the wolf is usually a helper and a guide. We also find myths of deities in wolf form, like the goddess Morrigana appearing in wolf form, but was defeated by the hero Cú Chulainn - the 'Hound [or Wolf?] of Cuainn' (cf. The Táin). There is also the old Gaelic/Irish month faoilleach, which comes from faol or faol-chù, "wolf", i.e. the "Month of the Wolf", February (in other cultures it is often January: January/February are obviously a period in which wolves may be more present [mating period]). The pre-medieval 'Celtic World' is of course much larger, covering most of Europe for over one millennium, from the Hallstatt period down to late Antiquity. It is therefore no surprise that wolves probably played a different role in each local myth and local religion, though there might be some common denominator. Since religious affairs were not written down in ancient times (according to Caesar, in his "Gallic War / de bello Gallico", the druids did not allow this!), our knowledge of ancient Celtic mythology is largely based on iconographic representations in art and on coinage. We are really dealing with a jigsaw puzzle where most of the pieces are lost. Various objects provide important clues. For example, the wolf does appear on a number of coins in the Iron Age, for example among the Carnutes, but it is difficult to explain his mythical, religious role. See the coins below with a variety of wolf depictions. Celtic Cosmic WolvesIn several regions of pre-Roman Europe, the wolf iconography shows similarities to Norse mythology. As shown by Daphne Nash-Briggs (2010; 2017), the wolf seem to have a role similar to the mystical wolves in Norse mythology where the wolves Sköll and Hatti chase the moon and the sun across the sky, and will finally catch up and eat them, and Fenrir is said to kill Odin at Ragnarök at the end of the world (also cf. Green: 1998, 160). We seem to find depictions of these mythical stories also on Celtic coins. Often we see the wolf, with open mouth, in combination with a number of symbols, frequently depicting the moon and/or the sun. For example, a coin discovered at Saint-Germain-en-Laye depict «le loup mangeur de lune» (Hollard 1999) with the wolf being about to sink his teeth into the «moon» which is depicted as a crescent. Above the wolf, we sometimes find «solar horse»; the latter is often also depicted being chased by a wolf, sometimes a stylised wolf or composite animal (Nash Briggs 2010). Another, «moon-eating» wolf can be found, for example, on a stater from the Calvados area (3rd-2nd century BC; Nash-Briggs 2010, 2, fig. 1). The so-called Norfolk Wolf coins, from the territory of the Iceni in eastern Britain, provide a comparable iconography, like a «Norfolk Wolf A» stater (c. 56-53 BC) which shows a stylised wolf about to swallow the moon, represented as a lunar eclipse (Nash Briggs 2010 for discussion; cf. ibd.: Figs. 4, 12, 14). On other coins we fine the wolf, the sun and the moon together with other symbols, like a palm tree, serpent, eagle (e.g. BN no. 6925, from the Unelli; cf. Duval 1989: 385). But we should not conclude that wolves therefore have negative connotations.

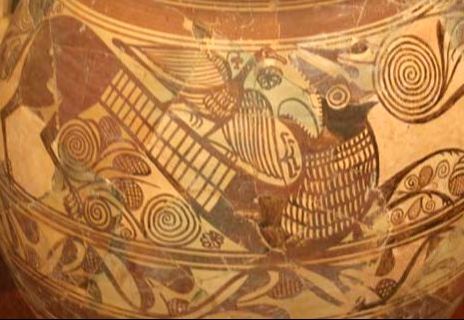

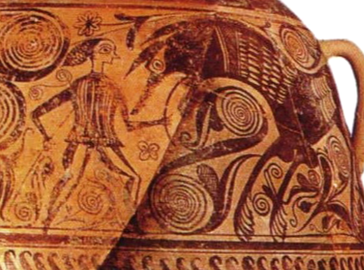

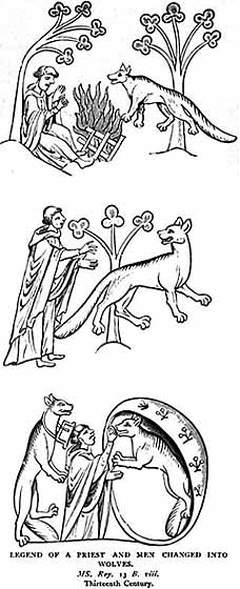

See Daphne Nash Briggs (2010), «Reading the images on Iron Age coins: 3. Some cosmic wolves», Chris Rudd List 3/110: 2-4. For the wolves in Norse mythology, see Wolf Myth Norse section! There is a lot of literature on 'Celtic' myth and religion, but wolves are rarely discussed. But see for example Miranda Aldhouse-Green, An Archaeology of Images: Iconology and Cosmology in Iron Age and Roman Europe. Iberian and Celtiberian wolf myths // Iberische Wolfsmythen // Dieux-loups iberiques et celtiberiques...A little excursion to the Iberian peninsula where we find populations that are categorised as Celts, Iberians and Celtiberians: Further Reading on Iberia: for example, Héctor Uroz Rodríguez, Practicas rituales, iconografía vascular y cultura material... Jorge García Cardiel ('El combate contre el mal', Complutum 25(1), 2014: 159-175) interprets the "wolf" as evil in Iberian iconography. But was this really the case? We really need to scrutinise the evidence for this. In the image of the wolf and the boy, below, are we really dealing with an image of an aristocrat fighting a mythical beast, in form of a wolf, presenting evil (cf. Cardiel 2014)? Or are modern scholars not influenced by their own cultural background, like the demonisation of the wolf in Christianity and in the last centuries in western Europe. Indeed, we may ask whether we may not be dealing with something quite different? After all, this comes from a period with relatively few proto-urban and urban settlements and a basically agricultural society. Once again, the wolf is likely to symbolise the perfect 'warrior', the instinctive forces of nature, symbolising 'the survival of the fittest'. The wolf is a guide, both in this life and in the afterlife. On the vase painting below we see the boy, the young/future warrior, standing face-to-face with a larger-than-life wolf. This does not represent a fight, especially when we consider the decoration of the entire vessell. Perhaps it shows a rite de passage (or coming-to-age ritual), as we have seen in so many other cultures (see e.g., José Carolos Fernandéz). We also should not forget the wolf's role as teacher, here perhaps for good hunting. Wolves in Medieval Celtic Ireland Celtic Ireland: Let's go back to Medieval Ireland. In Geralde de Barri's Topographia Hibernica (MS. Roy 13B.viii) from the 13th century AD), we find a story that has some resemblance to wolf myths in other cultures: humans turning to wolves for a certain period as well as wolves showing travellers the right way. The story tells of a priest travelling from Ulster to Meath in AD1182 who met a talking wolf. He told the priest that he came from Ossory (kingdom / diocese around Kilkenny), "on whose race lay an ancient curse whereby every seven years a man and a woman were transformed into wolves; at the end of seven years they recovered their proper form, and two other suffered a like transformation. He and his wife were the present victims of the course; his wife was at the point of death, and he prayed the priest to come and give her the viaticum' (i.e. the last rites / Holy Eucharist). The priest did it and the grateful wolf showed the priest the right road to Meath (cf. J.R. Green, Short history of the English People, II, London 1908, lxix-lxxx). Romano-British Divine Wolves: |

Sucellos - God with Wolf Skin? // Gott mit Wolfsfell //

This also leads us to an important South Gaulish deity, Sucellos, the "mallet god", sometimes wearing a wolf-skin and usually accompanied by what seems to be a dog (in the 1st-3rd century AD, when adopting the image of the Roman god Silvanus to represent their native deity, the Gauls also adopted the dog as the god's companion from Roman iconography; was it meant to symbolise a wolf?). Again, Sucellos is a chthonic god, like most deities (we also should not forget that, for example, mother goddesses are equally 'chthonic' in nature). And although this might have been the deity that Caesar interpreted as Dispater, Sucellos is more than just a god of the underworld; he can also be a healing deity (e.g. at Glanum, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence). We see wolves closely associated with a powerful Celtic (or Gallo-Roman) god. Unfortunately, as is common in Antiquity, all these pieces of evidence are still not sufficient to create a precise understanding of the associated myths and religious significance. Although a certain image of wolf and deity/deities emerges in the Celtic world, we are still far away from really understanding what is happening here.

Curchin, in his Romanization of Central Spain, also reminds of other pieces of evidence: like Appian (Iberica 48) mentioning a Celtiberian herald who wears a wolf-skin; and Francisco Marco Simón (1991: 96) discusses vases from Numantia wearing wolf skins. Paralells with Sucellos are perhaps less likely, but the wearing of wolf skins obviously had "magical" roles in numerous cultures.

Curchin, in his Romanization of Central Spain, also reminds of other pieces of evidence: like Appian (Iberica 48) mentioning a Celtiberian herald who wears a wolf-skin; and Francisco Marco Simón (1991: 96) discusses vases from Numantia wearing wolf skins. Paralells with Sucellos are perhaps less likely, but the wearing of wolf skins obviously had "magical" roles in numerous cultures.

Cernunnos on a Wolf (?)

Also see Gundestrup cauldron depictions, above

God with Wolf Skin

Celtic Wolf Children: Cormac Mac Airt

Similar to the Romulus & Remus story in Rome, we also find some "Wolf Children" in Celtic Mythology. For example, in Irish mythology, for example, we find king Cormac Mac Airt who was adopted and reared by a she-wolf with her cubs in the caves of Keash (County Sligo).

Of course, we should not ignore the more recent stories of "feral children", raised by wolves, like the famous (and dubious) case of Kamala and Amala in the 1920's (see Singh and Zingg, Wolf-Children and Feral Man, 1942 and one of the critical reviews) - probably a story as unbelievable as Rudyard Kipling's Mowgli in his Jungle Book from 1894. But perhaps not? After all, there seem to be countless stories of this kind across time and space! - Can they be all a hoax...?

Of course, we should not ignore the more recent stories of "feral children", raised by wolves, like the famous (and dubious) case of Kamala and Amala in the 1920's (see Singh and Zingg, Wolf-Children and Feral Man, 1942 and one of the critical reviews) - probably a story as unbelievable as Rudyard Kipling's Mowgli in his Jungle Book from 1894. But perhaps not? After all, there seem to be countless stories of this kind across time and space! - Can they be all a hoax...?

Scythia: wolf shape-shifters

Talking about 'shape-shifters', this story is interesting. The 5th-century BC Greek historian Herodotos (4.105) has recorded a story he heard about the Neuri who are said to have lived north of Scythia (roughly northern Ukraine, southern Belarus today): "It may be that these people are wizards; [2] for the Scythians, and the Greeks settled in Scythia, say that once a year every one of the Neuri becomes a wolf for a few days and changes back again to his former shape. Those who tell this tale do not convince me; but they tell it nonetheless, and swear to its truth". But perhaps we need to understand Herodotos' story quite differently: "becoming a wolf for a few days" could be part of an annual ritual, a 'rite de passage', perhaps comparable with NW American Indians (see page 2 of website).

Taboo words & wolf people

One linguistic note: one can notice over and over again that wolves are not always called wolves (and that terminology changes in many languages... the original word might get limited to a mythical context, or even tabooed, while new words develop to describe contemporary, mortal wolves. The word for dog is also used as a metaphor for wolves!

- We have seen in Japan (see Japan Wolf Deities page):

- inu = dog,

- Oinusama = "Honourable 'Dog' Deity";

- Yamainu = "Mountain Dog", etc..

- Also see above for the ancient Celtic word cuno which describes both wolves and dogs during the Roman period (cf. Delamarre, Dictionaire de la langue gauloise. 2003).

- And similar to Japanese, we find these taboo/metaphors for WOLF also, for example, in Latvian: dieva suns = "god dog" or meza suns = "forest dog" (cf. Gamkrelidze & Ivanov, Indo-European, p. 415.

- the Lukani in Southern Italy

- the Illyrian Daúnioi (also Daúnion teîkhos "wolf wall")

- the Dacian dáoi, "wolves".

- In Asia Minor (m. Turkey), names might go back to Hittite lukka "wolf", like Lukósoura and perhaps Lykaonia.

- There is also the Sarmatian tribe called Oûrgoi, "wolves" (Iranian) and the Phrzgian Orka/Orko (cf. Gamkrelidze et al. op. cit., p.416).

- For Celtic names of "wolf people", see the entry "cuno" in Xavier Delamarre 2003, Dictionaire de la langue gauloise

- Also see section on North America, e.g. the Pawnee as "wolf people".

Reviews

No customer reviews for the moment.