No products

Religious Art

New products

-

Seth vs Osiris, Ancient Egypt Metallic Original Art Solid Brass Collectible Mens' Watch

40 mm solid brass casing in gold finish with stainless steel back...

$ 121.44 -

Chinese Traditional Good Luck Dragon Art Gold Medallion Solid Brass Men's Watch

40 mm solid brass casing in gold finish with stainless steel back...

$ 129.59 -

English Colours Fire-Breathing Dragon Ancient Parchment Fantasy Art Brass Watch

40 mm solid brass casing in gold finish with stainless steel back...

$ 137.74 -

Ancient Blue Fire-Breathing Dragon Parchment Art Solid Brass Mens Dress Watch

40 mm solid brass casing in gold finish with stainless steel back...

$ 137.74 -

Golden Dragon Metallic Art Solid Brass Collectible Men's Fantasy Good Luck Watch

40 mm solid brass casing in gold finish with stainless steel back...

$ 121.44

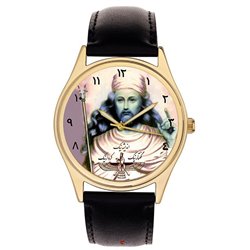

Zoroaster Zarathushtra Persian Parsi Prophet Devotional Wrist Watch

REL-022

New product

- impressive 40 mm solid brass casing with stainless steel back

- premium 2040 quartz movement.

- original parchment art acrylic dial

- waterproof bracelet with brass buckle

- 1 year warranty

More info

The date of Zoroaster, i.e., the date of composition of the Old Avestan gathas, is unknown. Classical writers such as Plutarch proposed dates prior to 6000 BC.[9] Dates proposed in scholarly literature diverge widely, between the 18th and the 6th centuries BC.

Until the late 17th century, Zoroaster was generally dated to about the 6th century BC, which coincided with both the "Traditional date" (see details below) and historiographic accounts (Ammianus Marcellinus xxiii.6.32, 4th century AD). However, already at the time (late 19th century), the issue was far from settled.

The "Traditional date" originates in the period immediately following Alexander the Great's conquest of the Achaemenid Empire in 330 BC. The Seleucid kings who gained power following Alexander's death instituted an "Age of Alexander" as the new calendrical epoch. This did not appeal to the Zoroastrian priesthood who then attempted to establish an "Age of Zoroaster." To do so, they needed to establish when Zoroaster had lived, which they accomplished by counting back the length of successive generations[11] until they concluded that Zoroaster must have lived "258 years before Alexander." This estimate then re-appeared in the 9th- to 12th-century texts of Zoroastrian tradition,[c] which in turn gave the date doctrinal legitimacy, especially since it was made plausible also by the observational history of the Pleiades in the Geoponica that indicates Zoroaster as a principal source of some observations. In the early part of the 20th century, this remained the accepted date (subject to the uncertainties of the 'Age of Alexander'[d]) for a number of reputable scholars, among them Hasan Taqizadeh, a recognized authority on the various Iranian calendars, and hence became the date cited by Henning and others.

By the late 19th century, scholars such as Bartholomea and Christensen noted problems with the "Traditional date," namely in the linguistic difficulties that it presented. The Old Avestan language of the Gathas (which are attributed to the prophet himself) is still very close to the Sanskrit of the Rigveda. Therefore, it seemed implausible that the Gathas and Rigveda could be more than a few centuries apart, suggesting a date for the oldest surviving portions of the Avesta of roughly the 2nd millennium BC.

A date of 11th or 10th century BC is sometimes considered among Iranists, who in recent decades found that the social customs described in the Gathas roughly coincide with what is known of other pre-historical peoples of that period.[citation needed] Supported by this historical evidence,[citation needed] the "Traditional date" can be conclusively ruled out, and the discreditation can to some extent be supported by the texts themselves: The Gathas describe a society of bipartite (priests and herdsmen/farmers) nomadic pastoralists with tribal structures organized at most as small kingdoms. This contrasts sharply with the view of Zoroaster having lived in an empire, at which time society is attested to have had a tripartite structure (nobility/soldiers, priests, and farmers). Although a slightly earlier date (by a century or two) has been proposed on the grounds that the texts do not reflect the migration onto the Iranian Plateau, it is also possible that Zoroaster lived in one of the rural societies that remained in Central Asia.

Place

Yasna 9 & 17 cite the Ditya River in Airyanem Vaējah (Middle Persian Ērān Wēj) as Zoroaster's home and the scene of his first appearance. The Avesta (both Old and Younger portions) does not mention the Achaemenids or of any West Iranian tribes such as the Medes, Persians, or evenParthians.

However, in Yasna 59.18, the zaraϑuštrotema, or supreme head of the Zoroastrian priesthood, is said to reside in 'Ragha'. In the 9th- to 12th-century Middle Persian texts of Zoroastrian tradition, this 'Ragha'—along with many other places—appear as locations in Western Iran. While the land of Media does not figure at all in the Avesta (the westernmost location noted in scripture is Arachosia), the Būndahišn, or "Primordial Creation," (20.32 and 24.15) puts Ragha in Media (medieval Rai). However, in Avestan, Ragha is simply a toponym meaning "plain, hillside."[12]

Apart from these indications in Middle Persian sources which are open to interpretations, there are a number of other sources. The Greek and Latin sources are divided on the birthplace of Zarathustra. There are many Greek accounts of Zarathustra, referred usually as Persian or Perso-Median Zoroaster. Moreover they have the suggestion that there has been more than one Zoroaster.[13] On the other hand, in post-Islamic sources Shahrastani (1086–1153) an Iranian writer originally from Shahristān, present-day Turkmenistan, proposed that Zoroaster's father was fromAtropatene (also in Medea) and his mother was from Rey. Coming from a reputed scholar of religions, this was a serious blow for the various regions who all claimed that Zoroaster originated from their homelands, some of which then decided that Zoroaster must then have then been buried in their regions or composed his Gathas there or preached there.[14][15] Also Arabic sources of the same period and the same region of historical Persia consider Azerbaijan as the birthplace of Zarathustra.[16]

By the late 20th century, most scholars had settled on an origin in Eastern Iran and/or Afghanistan. Gnoli proposed Sistan (though in a much wider scope than the present-day province) as the homeland of Zoroastrianism; Frye voted for Bactria and Chorasmia;[17] Khlopin suggests theTedzen Delta in present-day Turkmenistan.[18] Sarianidi considered the BMAC region as "the native land of the Zoroastrians and, probably, of Zoroaster himself."[19] Boyce includes the steppes to the west from the Volga.[20] The medieval "from Media" hypothesis is no longer taken seriously, and Zaehner has even suggested that this was a Magi-mediated issue to garner legitimacy, but this has been likewise rejected by Gershevitch and others.

The 2005 Encyclopedia Iranica article on the history of Zoroastrianism summarizes the issue with "while there is general agreement that he did not live in western Iran, attempts to locate him in specific regions of eastern Iran, including Central Asia, remain tentative."

Life

The Gathas contain allusions to personal events, such as Zoroaster's triumph over obstacles imposed by competing priests and the ruling class. They also indicate he had difficulty spreading his teachings, and was even treated with ill-will in his mother's hometown. They also describe familiar events such as the marriage of his daughter, at which Zoroaster presided. In the texts of the Younger Avesta (composed many centuries after the Gathas), Zoroaster is depicted wrestling with thedaevas and is tempted by Angra Mainyu to renounce his faith (Yasht 17.19; Vendidad 19). The Spend Nask, the 13th section of the Avesta, is said to have a description of the prophet's life. [22] However, this text has been lost over the centuries, and it survives only as a summary in the seventh book of the 9th-century Dēnkard. Other 9th- to 12th-century stories of Zoroaster, as in the Shāhnāmeh, are also assumed to be based on earlier texts, but must be considered as primarily a collection of legends. The historical Zoroaster, however, eludes categorization as a legendary character.

Zoroaster was born into the priestly family of the Spitamids and his ancestor Spitāma is mentioned several times in the Gathas. His father's name was Pourušaspa, or "Poroschasp," a noble Persian, and his mother's was Dughdova (Duγδōuuā). With his wife, Huvovi (Hvōvi), Zoroaster had three sons, Isat Vastar, Uruvat-Nara and Hvare Ciϑra; three daughters, Freni, Pourucista and Triti.[23] His wife, children and a cousin named Maidhyoimangha, were his first converts after his illumination from Ahura Mazda at age 30. According to Yasnas 5 & 105, Zoroaster prayed to Anahita for the conversion of King Vištaspa,[24] who appears in the Gathas as a historical personage. In legends, Vištaspa is said to have had two brothers as courtiers, Frašaōštra and Jamaspa, and to whom Zoroaster was closely related: his wife, Hvōvi, was the daughter of Frashaōštra, while Jamaspa was the husband of his daughter Pourucista. The actual role of intermediary was played by the pious queen Hutaōsa. Apart from this connection, the new prophet relied especially upon his own kindred (hvaētuš).

Zoroaster's death is not mentioned in the Avesta. In Shahnameh 5.92,[25] he is said to have been murdered at the altar by the Turanians in the storming of Balkh.

Death[edit]

Zoroaster's death was said to have been in Balkh located in present-day Afghanistan during the Holy War between Turan and the Persian empire in 583 BC.[26] Jamaspa, his son-in-law, then became Zoroaster's successor.[27]

Philosophy

In the Gathas, Zoroaster sees the human condition as the mental struggle between aša (truth) and druj (lie). The cardinal concept of aša—which is highly nuanced and only vaguely translatable—is at the foundation of all Zoroastrian doctrine, including that of Ahura Mazda (who is aša), creation (that is aša), existence (that is aša) and as the condition for Free Will.

The purpose of humankind, like that of all other creation, is to sustain aša. For humankind, this occurs through active participation in life and the exercise of constructive thoughts, words and deeds.

Elements of Zoroastrian philosophy entered the West through their influence on Judaism and Middle Platonism and have been identified as one of the key early events in the development of philosophy.[28] Among the classic Greek philosophers, Heraclitus is often referred to as inspired by Zoroaster's thinking.[29]

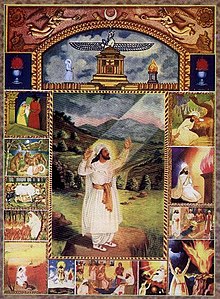

Iconography[edit]

Although a few recent depictions of Zoroaster show the prophet performing some deed of legend, in general the portrayals merely present him in white vestments (which are also worn by present-day Zoroastrian priests). He often is seen holding a baresman (Avestan; Middle Persian barsom), which is generally considered to be another symbol of priesthood, or with a book in hand, which may be interpreted to be the Avesta. Alternatively, he appears with a mace, the varza—usually stylized as a steel rod crowned by a bull's head—that priests carry in their installation ceremony. In other depictions he appears with a raised hand and thoughtfully lifted finger, as if to make a point. Zoroaster is rarely depicted as looking directly at the viewer; instead, he appears to be looking slightly upwards, as if beseeching. Zoroaster is almost always depicted with a beard, this along with other factors bearing similarities to 19th-century portraits of Jesus.[30]

A common variant of the Zoroaster images derives from a Sassanid-era rock-face carving. In this depiction at Taq-e Bostan, a figure is seen to preside over the coronation of Ardashir I or II. The figure is standing on a lotus, with a baresman in hand and with a gloriole around his head. Until the 1920s, this figure was commonly thought to be a depiction of Zoroaster, but in recent years is more commonly interpreted to be a depiction of Mithra. Among the most famous of the European depictions of Zoroaster is that of the figure in Raphael's 1509 The School of Athens. In it, Zoroaster and Ptolemy are having a discussion in the lower right corner. The prophet is holding a star-studded globe.

Reviews

No customer reviews for the moment.